CRISPR Explained

What is CRISPR-Cas9? Why is it used for gene editing? This article answers the big questions and explains how CRISPR works in nature and in the lab...

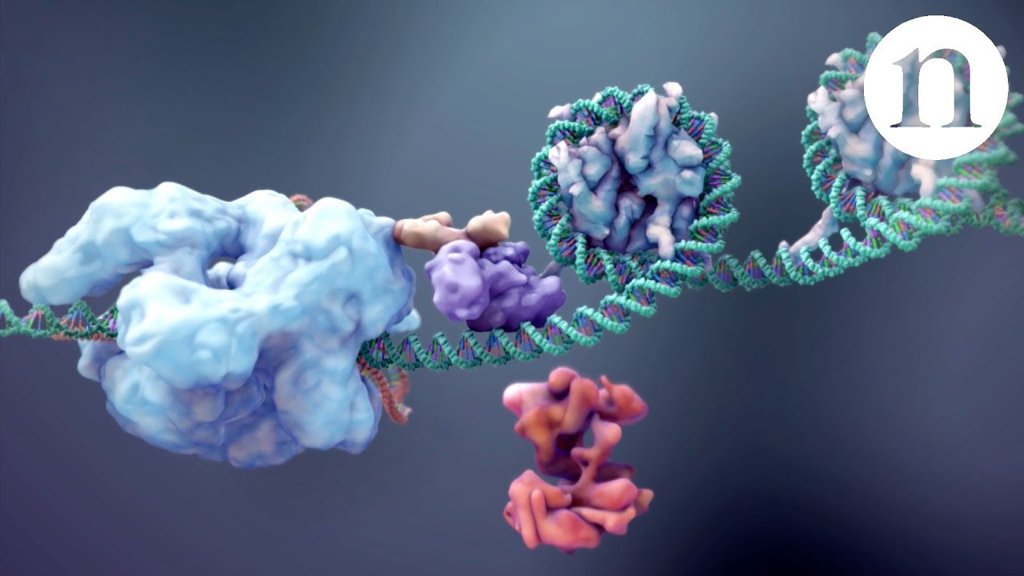

CRISPR: Gene editing and beyond (video by Nature on YouTube)

CRISPR: Gene editing and beyond (video by Nature on YouTube)

What is CRISPR/Cas?

CRISPR stands for 'Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats', a sequence of chemical letters in DNA. Cas means 'CRISPR-associated protein'. There are numerous Cas proteins with various functions: Cas9 is an enzyme that cuts specific sites in DNA, for example. CRISPR sequences and Cas proteins work in combination as a CRISPR-Cas system, which is often abbreviated to just CRISPR and pronounced "crisper".

Why is CRISPR important?

CRISPR-Cas is a natural defence system used by microbes that scientists have turned into tools for molecular biology. The most famous application is CRISPR genome editing -- targeting a specific DNA sequence to delete or insert genetic material such as new genes at that precise location. One CRISPR definition is 'A segment of DNA containing short repetitions of base sequences, involved in the defence mechanisms of prokaryotic organisms to viruses.' The CRISPR acronym is also short for CRISPR gene editing ('A genetic engineering tool that uses a CRISPR sequence of DNA and its associated protein to edit the base pairs of a gene') and so artificial CRISPR-Cas systems are also known simply as 'CRISPR'.

How does CRISPR work?

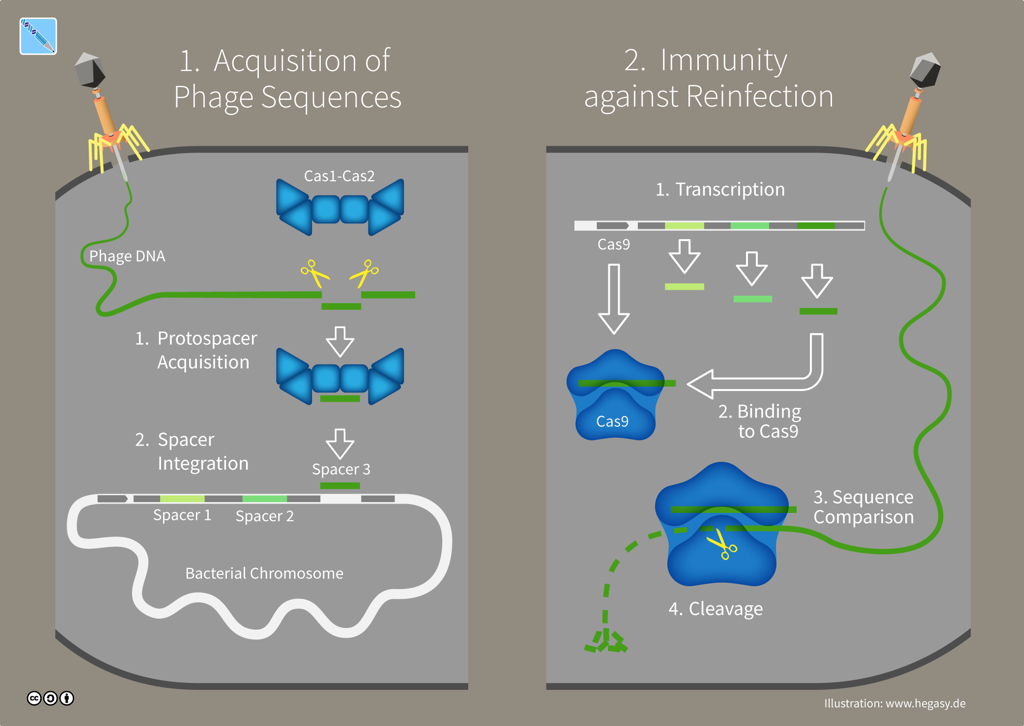

In bacteria and archaea -- single-celled microorganisms without a nucleus collectively named prokaryotes -- CRISPR-Cas is an adaptive immune system. CRISPR-Cas systems provide antiviral defences that remember and adapt to viruses or 'phages'. After a phage invades a microbe and injects its genome, that virus' genetic material is chopped-up by enzymes in the cell. Cas proteins such as Cas1 and Cas2 then paste bits of viral genes into the microbe's DNA, which leaves a genetic memory called a 'spacer' sequence. If another virus attacks, the microbe can quickly copy that DNA spacer into an RNA molecule which a protein like Cas9 will use as a guide to recognize and destroy the invader's genome.

CRISPR-Cas immunity in bacteria (illustration CC BY-SA 4.0 Guido Hegasy)

CRISPR-Cas immunity in bacteria (illustration CC BY-SA 4.0 Guido Hegasy)

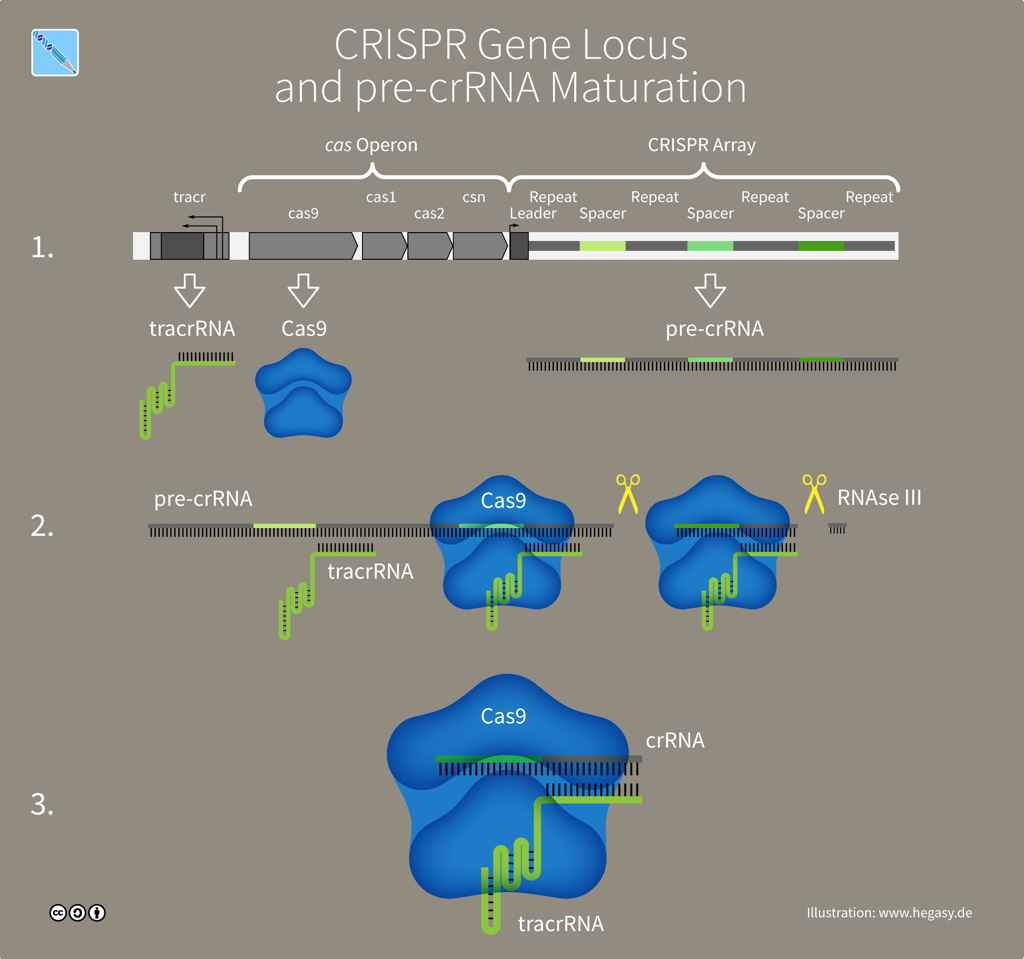

What is a CRISPR locus?

The genetic information that produces a CRISPR-Cas system is found at a single genomic location or 'locus'. A CRISPR locus has two main parts: a cluster of genes encoding Cas proteins and the CRISPR array, which consists of between two and several hundred repeating sequences of DNA letters (each 25-35 letters long) separated by unique spacers -- genetic memories of past invaders (30-40 letters). Both the repeats and spacers in an array have interesting features: each DNA repeat is a partial palindrome (hence 'palindromic' in CRISPR) while spacers all share a common sequence called a Proto-spacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) that Cas9 requires to recognize its DNA target. The CRISPR-Cas9 locus has an essential accessory gene called 'tracr', four Cas genes and a CRISPR array.

The CRISPR-Cas9 locus (illustration CC BY-SA 4.0 Guido Hegasy)

The CRISPR-Cas9 locus (illustration CC BY-SA 4.0 Guido Hegasy)

What are crRNA, tracrRNA and sgRNA?

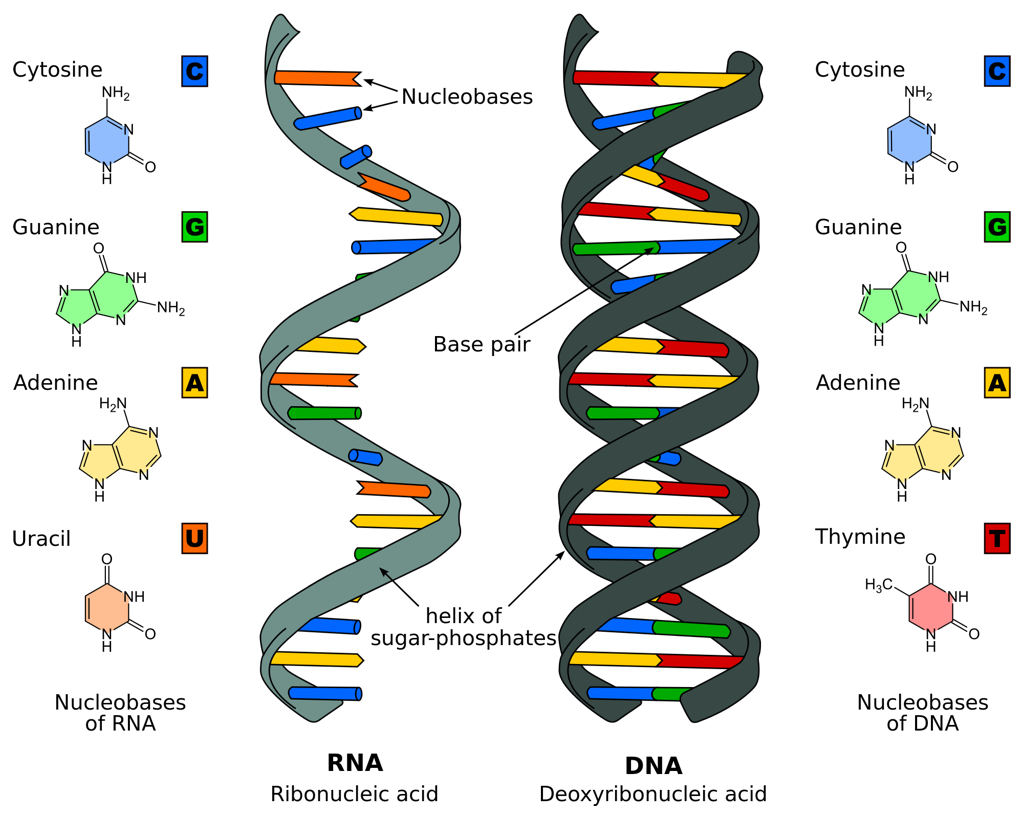

A CRISPR array contains spacer sequences whose genetic information is copied (through transcription) from DNA into molecules of CRISPR RNA or crRNA. Another DNA sequence in the array, the tracr gene, is also transcribed into a molecule called tracrRNA -- short for 'trans-activating CRISPR RNA'. The two RNA molecules, tracrRNA and crRNA, link to form the guide that Cas9 proteins use to recognize a DNA target. To create a simple synthetic tool for gene editing, scientists combined crRNA and tracrRNA into a single guide RNA, sgRNA.

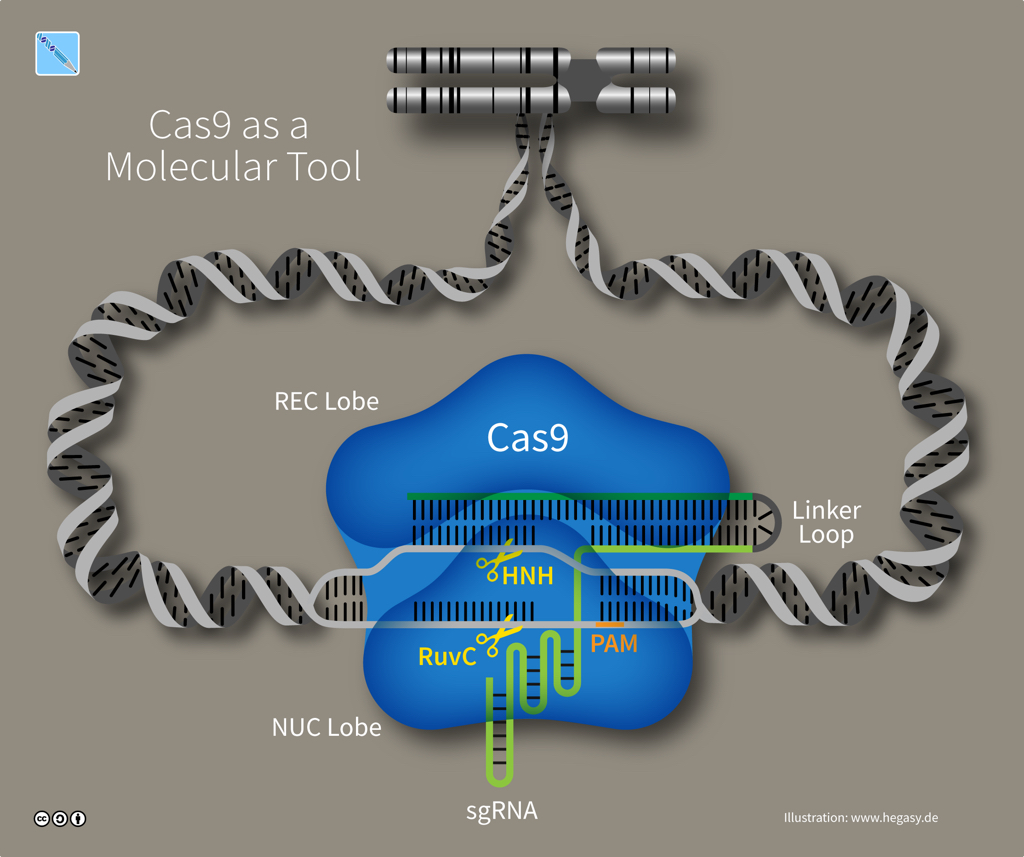

Cas9 tool and sgRNA (illustration CC BY-SA 4.0 Guido Hegasy)

Cas9 tool and sgRNA (illustration CC BY-SA 4.0 Guido Hegasy)

Why is Cas9 special?

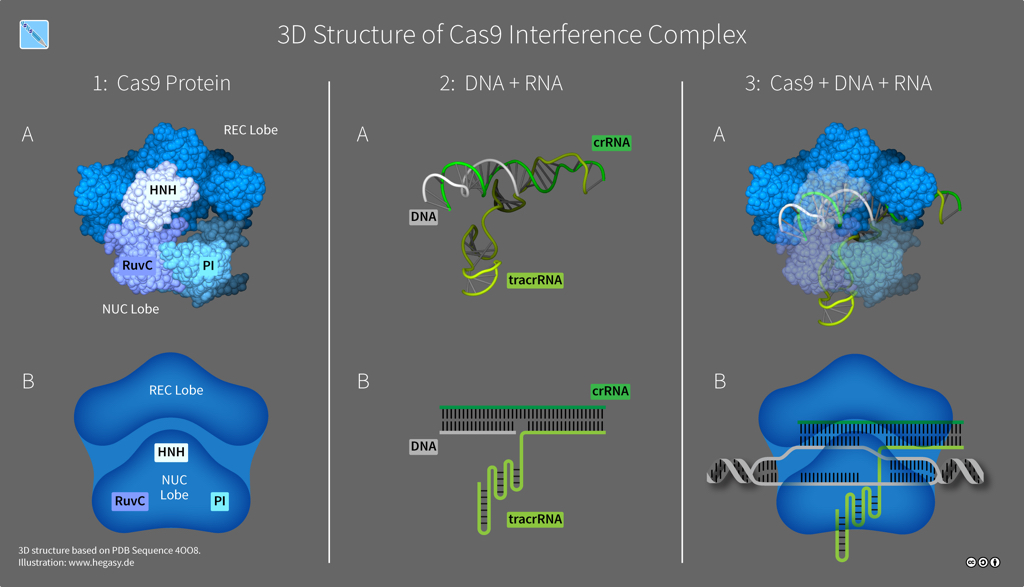

The exact number of Cas proteins is unknown, but based on the evolution of CRISPR-Cas systems, there are probably six distinct types. Type II systems use a single nuclease enzyme to slice a target DNA sequence, using an RNA guide molecule copied from a spacer. Cas9 is an RNA-guided nuclease that comes from Streptococcus species and is the only enzyme that a bacterium needs for cutting DNA to confer resistance against viruses. Whereas some CRISPR-Cas systems need multiple pairs of molecular scissors, Cas9 has two domains -- HNH and RuvC -- that each snip a strand in DNA's double helix, which is especially useful to researchers as it makes Cas9 an all-in-one solution for editing DNA.

Structure of Cas9 (illustration CC BY-SA 4.0 Guido Hegasy)

Structure of Cas9 (illustration CC BY-SA 4.0 Guido Hegasy)

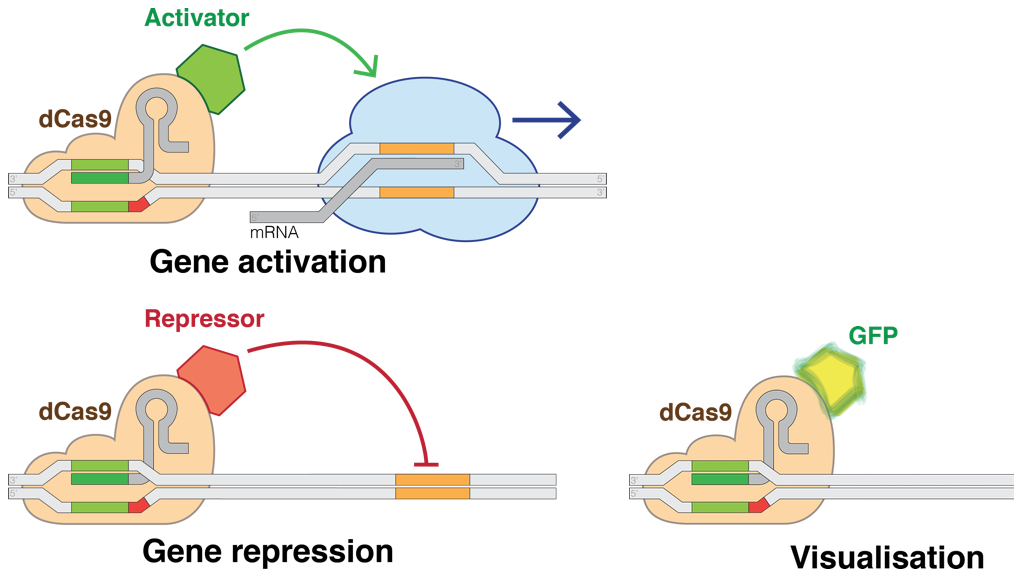

What is dCas9?

The CRISPR-Cas9 toolkit is used for more than editing genes. While the common 'wild type' form of the Cas9 protein snips both strands in DNA, there are also 'mutant' forms that serve as a nickase -- an enzyme that only nicks one strand. Another useful variant is 'dead Cas9' or dCas9, in which the HNH and RuvC domains have been mutated to deactivate its cutting ability, allowing the enzyme to target -- but not damage -- a DNA sequence. Coupled with custom guide RNA, a nuclease-deactivated dCas9 allows regulation of DNA in a sequence-specific way: a dCas9 protein enables activation and interference (CRISPRa and CRISPRi) or even total knockout (CRISPR KO) of gene expression by adding an activator or repressor domain. dCas9 can also find particular DNA sequences: adding a marker like Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) means it can be used to visualize and pinpoint where a gene is expressed inside the cell (subcellular localization).

dCas9 applications (illustration CC BY-SA 4.0 Marius Walter)

dCas9 applications (illustration CC BY-SA 4.0 Marius Walter)

How does Cas9 target specific DNA?

Besides cutting, the Cas9 protein also unzips the double-stranded structure to expose DNA's sequence of chemical letters or 'bases'. The RNA guide that Cas9 uses to recognize its target includes a single-stranded sequence that will match and pair with complementary bases on a target DNA. The matching sequence in an RNA guide is usually specific enough to a DNA that errors or 'off-target' cuts at other sites -- introducing unintended mutations -- are relatively rare.

Base pairs in RNA and DNA (illustration CC BY-SA 3.0 Sponk)

Base pairs in RNA and DNA (illustration CC BY-SA 3.0 Sponk)

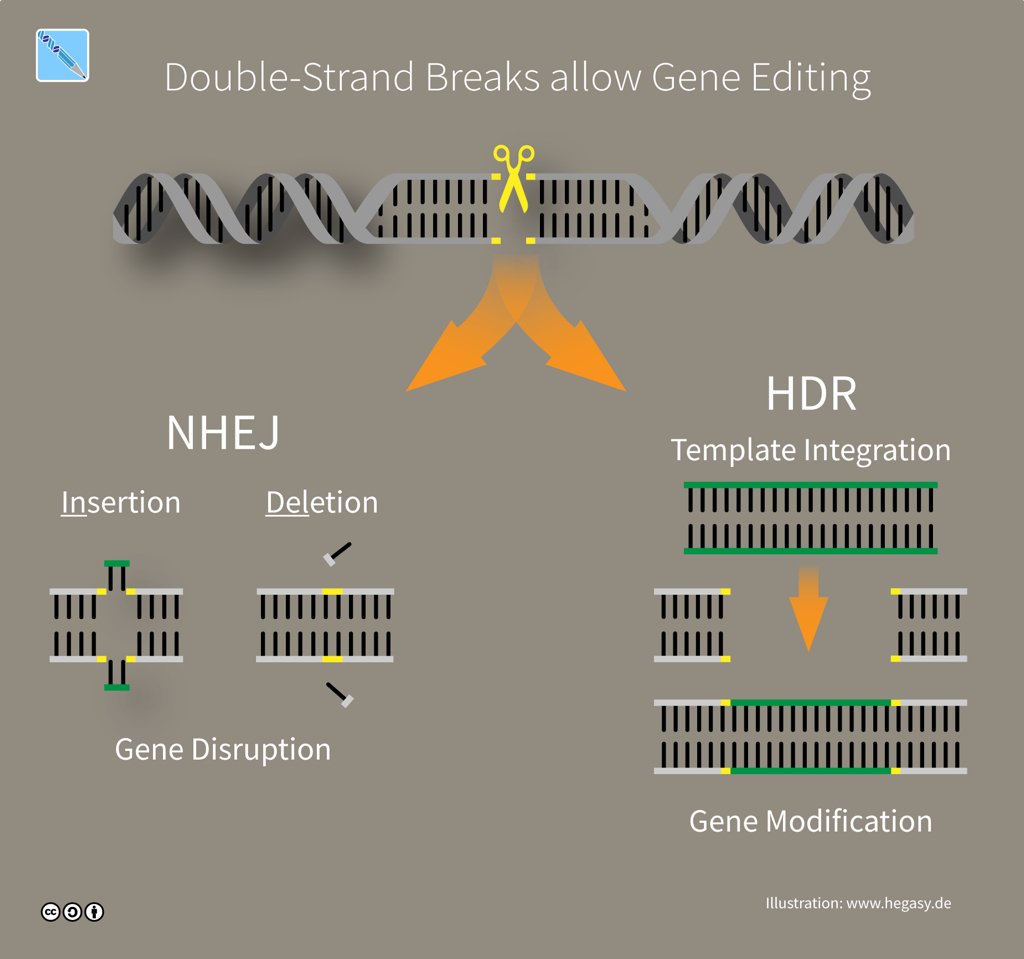

How does CRISPR gene editing work?

The CRISPR mechanism involves DNA repair. While the work of a microbe's defence system is done once it cuts foreign DNA, genome-editing tools must put the pieces back together again. Fortunately, cells can rely on repair machinery that will automatically try and fix double-strand breaks in DNA. If a cell can access a genetic sequence that's similar or 'homologous' to the broken DNA -- like the RNA guide carried by a Cas9 protein -- then the cell uses that matching sequence as a template to fill what it thinks is a missing piece by a process called Homology-Directed Repair (HDR). If a no template is available -- because a Cas9 tool was designed to cut but not edit -- then the cell fixes the damage by simply sticking the ends of DNA together through error-prone 'Non-Homologous End Joining' (NHEJ).

CRISPR editing via DNA repair (illustration CC BY-SA 4.0 Guido Hegasy)

CRISPR editing via DNA repair (illustration CC BY-SA 4.0 Guido Hegasy)

Who discovered CRISPR?

Two people could be considered discoverers: in 1987 Yoshizumo Ishino detected 'unusual DNA' in bacteria, which Francisco Mojica first characterized as repetitive DNA in archaea in 1993. But it wasn't until the mid-2000s that researchers realized that CRISPR-Cas is a widespread microbial immune system. According to one account of the history of CRISPR research, around a dozen groups gradually revealed CRISPR's various components. So you could also argue that no individual person or team should be credited with discovering CRISPR.

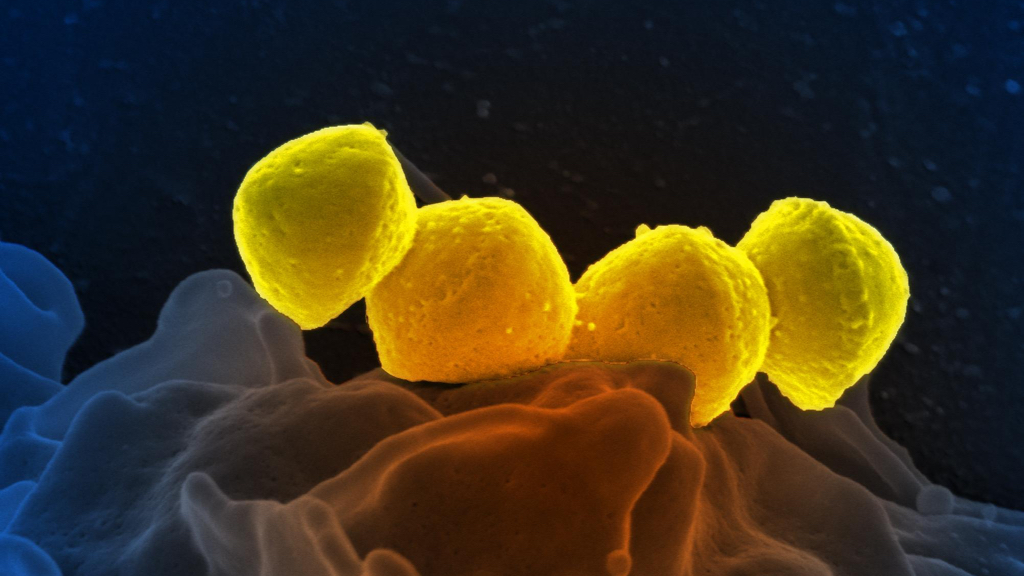

Streptococcus pyogenes on a human neutrophil cell (image CC BY-SA 2.0 NIAID)

Streptococcus pyogenes on a human neutrophil cell (image CC BY-SA 2.0 NIAID)

Who invented CRISPR technology?

Three people are frequently credited in media coverage and prestigious awards: structural biologist Jennifer Doudna, microbiologist Emmanuelle Charpentier and biochemist Virginijus Šikšnys. In 2012 Šikšnys showed you could design a custom crRNA guide to direct Cas9 to new targets, while Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna fused crRNA and tracrRNA to create sgRNA. The trio are the leading candidates to share a Nobel prize after winning the 2018 Kavli Prize in Nanoscience "for the invention of CRISPR-Cas9, a precise nanotool for editing DNA, causing a revolution in biology, agriculture, and medicine."

Jennifer Doudna, Virginijus Šikšnys and Emmanuelle Charpentier (photo CC BY-SA 2.0 NTNU Trondheim)

Jennifer Doudna, Virginijus Šikšnys and Emmanuelle Charpentier (photo CC BY-SA 2.0 NTNU Trondheim)

Who made the biggest CRISPR breakthrough?

Two contenders are bioengineer Feng Zhang and geneticist George Church. In 2013, both labs reported editing the complex cells of mammals, where the DNA is packaged within a hard-to-reach nucleus (today Cas9 can be engineered to include a Nuclear Localisation Sequence or NLS that helps the protein enter a mammalian cell nucleus). The issue of who should be cited for 'discovering' the tools remains controversial, partly due to an ongoing patent dispute over the technology. Many CRISPR breakthroughs were achieved through experiments performed by junior researchers in the labs of each principal investigator -- the unsung heroes of CRISPR who are rarely mentioned in a narrative about CRISPR's discovery.

Why is CRISPR revolutionary?

The CRISPR-Cas9 system is currently the most efficient and reliable tool for DNA editing. There are rival genome editors such as Zinc-Finger Nuclease (ZFN) enzymes and Transcription Activator-Like Effector Nucleases (TALENs), but none have proven to be as effective at making precise genetic changes -- at least to date. One big advantage of CRISPR is that, whereas genome editors based on ZFNs or TALENs must be improved by mutating the protein, Cas9's ability to target DNA can be easily reprogrammed by genetically engineering its guide RNA sequences.

What are the challenges of CRISPR?

CRISPR science isn't perfect. One technical limitation is that, although CRISPR is more accurate than other editors, it can still cut the wrong places in DNA, resulting in undesirable off-target effects that can disable other genes. Another challenge is ethical: what impact will CRISPR have on society? The tool is powerful yet accessible, and already researchers have reportedly used it on humans to create so-called CRISPR babies. As a consequence, some prominent scientists have called for a global moratorium (but not ban) on heritable genome editing in clinical settings to produce genetically-modified children.

What are CRISPR therapeutics?

Although CRISPR technology has many potential applications, arguably the most exciting is in CRISPR gene therapy: editing a human genome to correct mutations that cause diseases such as muscular dystrophy. CRISPR tools are also used widely in biomedical studies to create genetically-modified organisms that act as more realistic animal models for studying cancer. Those are some of the many examples of how CRISR-Cas9 technology is improving scientific research and human health.

This feature was written by JV Chamary PhD for Novatein Biosciences, a company that supplies products and services for CRISPR-Cas9 research projects.